Originally published in the July 2019 issue of (614) Magazine

It’s difficult to fathom in the age of a thousand channels — not to mention Netflix, Amazon, and Hulu — a single moment when the entire world was watching the same thing at the same time on television. But in July of 1969, nearly every set was tuned in to watch human history unfold.

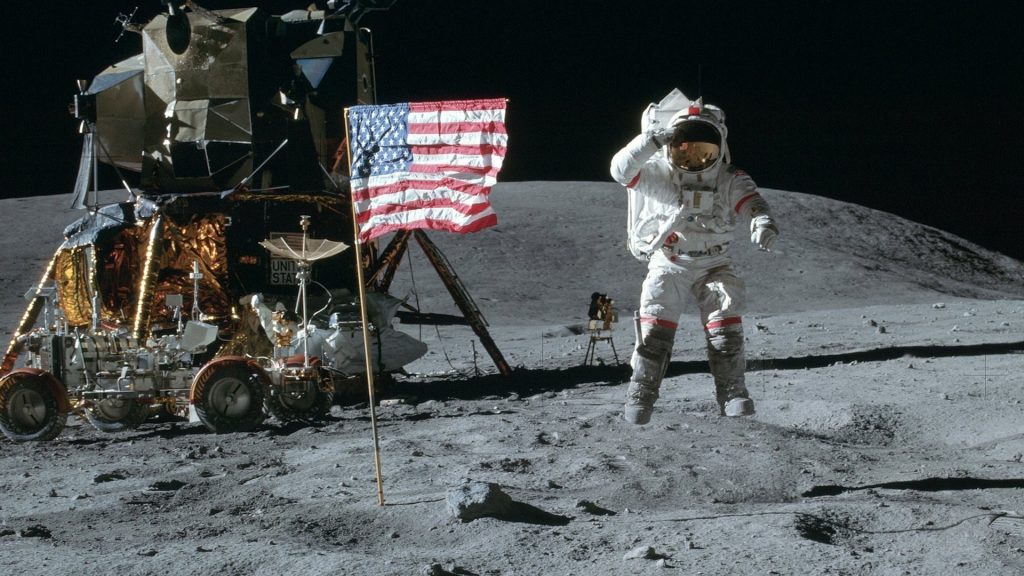

Five decades is a long time to forget, and grainy footage and faded photos let memories dim and make the achievement sometimes seem more distant than the Moon itself. It was Ohio’s own John Glenn who first took Americans into space, and Neil Armstrong who placed that first footprint on the lunar surface. So it was only fitting that two guys from Ohio would once again astound audiences with the imagery and adrenaline of that fabled first step on our nearest celestial neighbor.

Todd Douglas Miller and Matt Morton grew up together in Gahanna and have known each other since grade school. Their short-lived high school band played a few graduation gigs, but when it came time for college, they parted ways yet remained creatively connected. Miller moved to Michigan for film school, but when his student documentary set in their hometown needed some songs to round it out, Morton’s college band he’d formed at Denison University supplied the soundtrack. It was their first filmmaking collaboration, but hardly their last.

At this year’s Sundance Film Festival, their latest project, Apollo 11, stunned the jury and the industry with long-forgotten, large-format footage that made the Moon launch look like it happened yesterday. They’d set out to make a movie, but created a time machine.

“When we first contacted the National Archives about transferring every frame of film they had from Apollo 11, I’m sure they thought I was nuts,” recalled Miller. He knew the task was so daunting that no one in half a century had dared to even consider it. “About three months into the project, they wrote us an email with a progress report on everything they had in 16mm and 35mm from their NASA collection. But buried in the middle of the message was this discovery of 65mm Panavision footage. We didn’t know how much or the condition at the time, but it looked promising.”

“Promising” is polite parlance for unknown, but optimistic. Some of the reels had dates, a few even had shot lists. Others just had Apollo 11. It was an uncataloged mess by studio standards, but an untouched tomb of priceless artifacts to Miller and his team.

“The parallel story is that the post production facility I’d been working with in New York for a very long time was just getting into the film scanning business when a lot of companies were getting out,” Miller explained. “They were developing technologies that could handle large format film up to 70mm. The stars really did align.”

In an earlier era of film before a stream of electrons delivered pristine pictures and sound, images and audio weren’t one product until a film was edited and printed for exhibition. Apollo 11 curates thousands of hours of both down to an hour and a half opus using raw materials and equipment designed specifically for the project, most of it never seen or heard before. Miller and the team worked for weeks in three shifts, 24 hours a day, scanning each frame, and divvying up 11,000 hours of mission control and flight recordings to match up to footage later.

“We copied all of the files and just put them on our phones. My producing partner had this knack for finding these little moments of humanity. Our office is between our two houses. It was just a short walk for both of us, so we’d listen on the way,” Miller recalled. “I’d show up having just listened to 15 minutes of static and he’d have this revelation captured from the onboard audio of this song, Mother Country, which we ended up editing into the film. He also found audio of a woman’s voice who was a backroom flight controller arguing with one of the front room controllers about the return trajectory. Researchers and historians are going to spend decades on just the audio.”

But even the rich texture of images and conversations lacked the palpable tension necessary to pull everything together and put the achievement of Apollo 11 in the proper context for audiences. Luckily, Miller already had someone in mind working side-by-side from the start.

“When we did the first test screening, we basically had footage of the astronauts suiting up leading right up to the launch and the liftoff,” explained Matt Morton, who composed the entire score from his basement studio in Hilliard. “But what stuck with me most was the look, not of fear, but the sense of duty and the weight on their shoulders. I scored it with the same reverence and gravity, in that moment when they didn’t know, when none of us knew, if they were going to make it.”

Echoing the images and audio required rethinking the way the two had worked previously on several shorts, commercial projects, even acclaimed documentaries like Dinosaur 13 and The Last Steps, which chronicled NASA’s final mission to the Moon. Morton wanted something old, but original.

“When I told Todd I only wanted to use pre-1969 instruments, and most of the sound to come from an old Moog synthesizer, he needed some convincing,” chided Morton. “I try to stimulate discussion with all of my clients, offering suggestions and perspective from my take on the project. But Todd and I have this shorthand. I know how he feels about different styles of music down to the instruments. We can be honest.”

The result is an immersive experience that puts audiences of any age on the launch pad, in the lunar capsule, and on the Moon with unprecedented authenticity. The whole film feels almost voyeuristic with a direct cinema style that’s been all but abandoned in favor of contemporary cut rates and CGI. But perhaps most notable are the reaction shots throughout. If 2001: A Space Odyssey was Stanley Kubrick’s vision of mankind venturing into the unknown void, then this could be Steven Spielberg’s, amplified by a score as deceptively complex and unnerving as any science-fiction thriller.

The enormity of Apollo 11 begs for the biggest screen possible. Both Miller and Morton recalled fond memories of field trips to COSI as kids and the curiosity it helped foster, which comes full circle with a special 47-minute museum cut now screening at COSI’s IMAX theater throughout the summer—just the right length for aspiring astronauts and aerospace engineers. The full 93-minute cut will air on CNN July 20 in honor of the 50th anniversary of the Moon landing. The score is available on CD and digital, but will have a special anniversary vinyl release as well.

Also worth noting, neither has any firsthand memory of the Moon landing. They’re barely old enough to remember the moonwalk. Apollo 11 is effectively a found footage documentary, one that could earn both Miller and Morton an Academy Award for a film shot entirely before either of them was born. Both were quick to quash such speculation, as sincere artists do, rewarded by the achievement, not the accolade. As with previous projects, inspiration remains a primary motivation.

“Just last week I was in Amsterdam for a premiere at the EYE Film Institute and learned they have 39,000 reels of film in their archive,” revealed Miller. “Future filmmakers should get out their flashlights. There’s a lot more footage waiting to be rediscovered.” ▩

Apollo 11 is back in theaters nationwide for limited IMAX engagements and is now available on Hulu.